English 101 Essay: The Grade Inflation Conundrum

Imagine having worked on an essay for many hours, reading all the source material and rubrics, thoughtfully creating a thesis, only to be given a less than stellar grade. Simultaneously your college dorm mate threw together an essay with minimal effort and received the same grade. They spent all week partying and hanging out with friends, while you labored with high hopes of positive results. There is a marked difference in the quality of the two essays, yet they receive the same grade. This is one of many problems with grade inflation. This is an examined topic by the two articles “Grade Inflation Gone Wild” by Stuart Rojstaczer and “Doesn’t Anybody Get a C Anymore?” by Phil Primack. Both authors state that grade inflation is a problem that has steadily grown since the 1960s. If there is going to be long-term upholding of academic integrity, then grade inflation is going to have to be a topic that is addressed.

In the essay “Doesn’t Anybody Get a C Anymore,” by Phil Primack, written in 2008, the author has taken a position perfectly understandable for someone who is a professor at Tufts University, a former teacher at Jonathan M Tisch College in Citizenship and Public Service as well as author of numerous articles including some published in the New York Times and Columbia Journal Review.

He tells a personal story of a student who put in a C level effort, was given the benefit of the doubt and granted an (undeserved) B and then complained that the student wanted an A. Primack was educated when an A meant excellent, a B meant good, a C meant average, a D meant below average, and an F meant fail. Years ago, grades were things earned by effort not granted by entitlement. Entitlement, seemingly gained by paying tuition.

Primack quotes Senator Hank Brown, a former university president, who lamented that giving grades that are not an A grade resulted in poor student evaluations of the teachers. He felt this lead to poorer teaching but happier students.

Primack also points to tuition being an issue. Expensive schools like Princeton had escalating levels of A grades to a point wherein 2004 47% of students received an A. Conversely, Wellesley has fought grade inflation, and their students have an average GPA of 3.3. At this school, your grade means something.

In the article ‘Grade Inflation Gone Wild’ by Stuart Rojstaczer, the author also a former professor (Duke University) and author of Gone for Good; Tales University Life after the Golden Age (1999), the same points are made and buttressed by actual data.

Rojstaczer directs the reader to his website, at which you can find several charts which he created from surveying many colleges and universities, both private and public.

In reviewing said charts, he admits his collection methods are not top-notch, but they do show a disturbing trend.

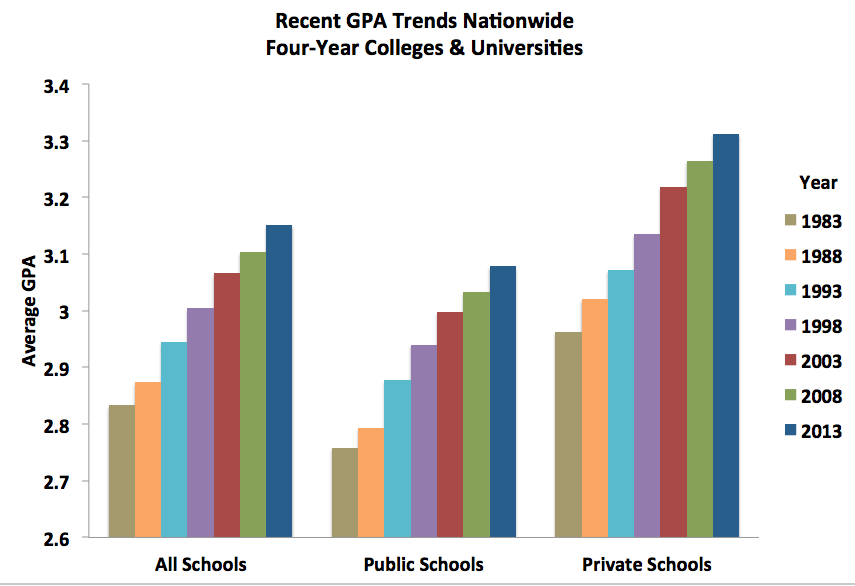

Fig. 1. Recent GPA Trends Nationwide. Four-Year Colleges & Universities. “Grade Inflation at American Colleges and Universities,” by Stuart Rojstaczer, 2016, gradeinflation.com. Accessed 28 March 2021.

While there is an obvious indication that the more expensive the school the looser the grading, it is still a problem for public schools (see fig. 1).

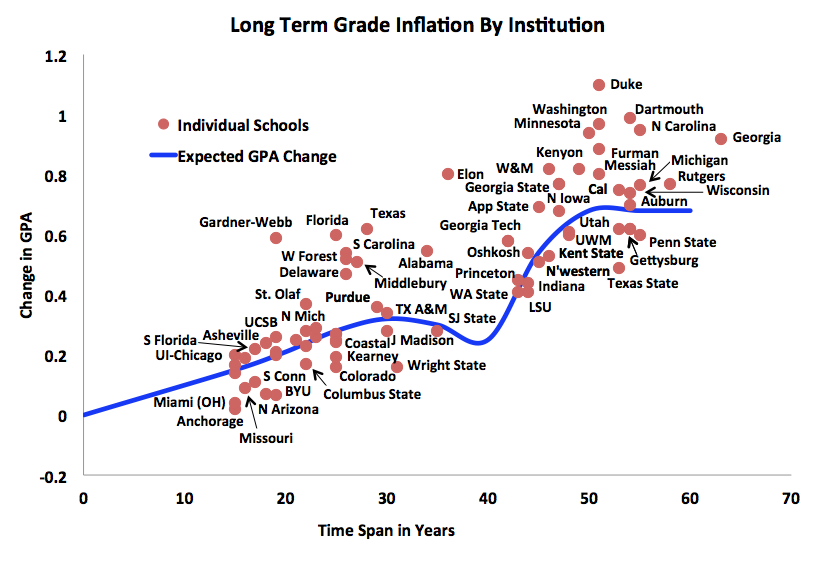

Fig. 2. Long Term Grand Inflation by Institution. “Grade Inflation at American Colleges and Universities,” by Stuart Rojstaczer, 2016, gradeinflation.com. Accessed 28 March 2021.

Data indicates that grades were inflated in the 1960’s, leveled out in the 1970s then went up in the 1980s and beyond (see fig. 2).

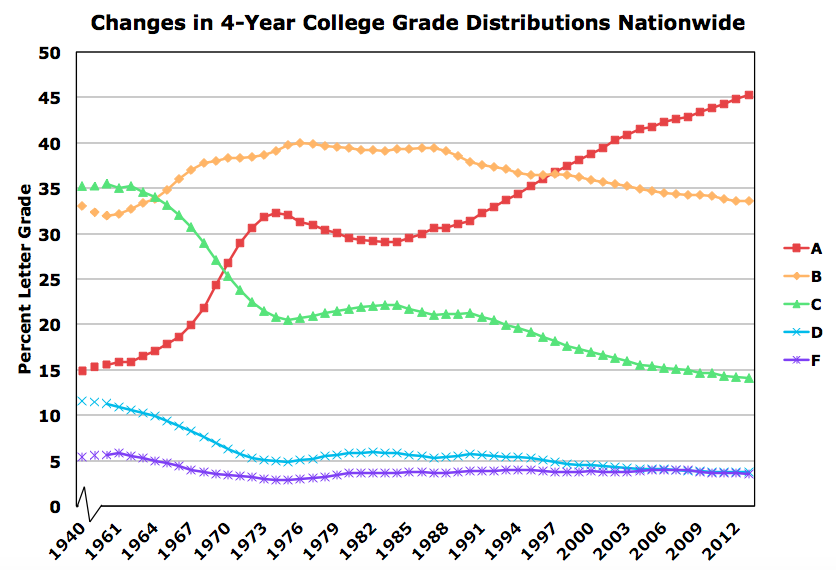

Fig. 3. Change in 4-Year College Grade Distributions Nationwide. “Grade Inflation at American Colleges and Universities,” by Stuart Rojstaczer, 2016, gradeinflation.com. Accessed 28 March 2021.

This chart, in particular, supports his point (see fig. 3).

Rojstaczer points out that students spend much less time studying than boozing, which is problematic in several ways. Clearly, the students are not learning as much, are dancing with the risk of alcoholism, do not take their studies seriously, and expect to get higher grades with less effort, forming and perfecting intellectual laziness and laziness in general.

He says it is a complex problem, but one with solutions. Essentially, his solutions are to admit there is a problem (hard to ignore) and implement a solution. That is so elementary it is almost laughable. What problem does any of us face that does not require seeing there is a problem and then looking for a solution?

So, are the arguments presented here valid arguments? The data so suggests. There is certainly a small mountain of data to gather to support that this is occurring and that it is a problem that begs to be addressed.

Neither author addresses the elephant in the room– what happens to these uneducated students when they graduate with their meaningless degrees, created by meaningless grades? Will they blame their soft-spined teachers for doing a poor job? Will they feel their money was misspent (okay, more likely daddy’s money). Will they find they are a problem employee because they do not put in any effort or enough effort and fail then blame their boss? At what point will they realize that effort will save their job, marriage, career?

Neither address the entitlement culture in which students (and others) somehow feel that they are entitled to something they have not earned. Frustrated persons are rampant in our society. Some have guns and use violence to express their frustration or blame the government or politicians or daddy and mom, or anyone who is doing better than they.

Professors are frustrated but compliant. Universities are complicit in a grab for dollars and applicants. Since the inflation does not begin at college, in grade school, we have a huge mass of unqualified, uneducated kids heading into upper-level classes well above their heads who then give them a pass.

Somehow, these kids then think they are well educated. In a way, they are, but it is the wrong lesson! Society now has a doctor who does a poor job of operating or a voter who does not understand basic civics, or a parent whose response to a whiny child is to give in to stay popular.

Primack’s essay was mostly opinion with an anecdotal quote in sympathy and agreement with his position. His is a ‘let us look at this’ piece.

Rojstaczer’s essay has more meat on the bones in terms of data and gives rise to a broader view of the topic. Money, the love of which, well, we all know, drives much of this issue. Universities want students and the money they bring. Big-money schools have big reputations, whether warranted or not, so junior wants that Yale diploma and Yale wants daddy happy enough to send more kids their way. Universities love donors, and a happy daddy makes a happy bank book. If Yale becomes known as a party school or a school which gives out A’s like candy on Halloween and is no longer known for academic excellence, the flow may end and the money dries up.

Employers will soon find out that a Yale or any other ivy league university degree has less academic value than a California State degree, and they can hire for a much smaller starting salary.

Additionally, when junior goes out into the real world and cannot point out where Canada is when his non-college graduated co-worker can, his embarrassment (assuming he has that component anymore in his personality) should be substantial and he should feel a component of shame and regret. One cannot simply shrug and say, “I guess I spent more time with Johnny Walker than with John Steinbeck at Yale.”

Reed College in Oregon, hardly a widely known college in the national or international scope of things, has held grades steady for 20 years. An employer looking at two applicants, assuming he or she was up on this topic, should take the Reed grad over the Yale applicant.

Also not addressed but relevant is that these schools famous for something they no longer have (excellent graduates) have been cranking out fancy diplomas pinned to uneducated graduates. Within the circle of educators, that is known.

One only has to look at some of the famous recent Ivy league graduates and wince at their abilities to do even rudimentary analysis. For example, many US senators who have Harvard or Yale degrees and cannot read and understand proposed legislation or understand the social situations that require change, and even some with law degrees who do not understand something as basic as the three forms of government. Anyone who has ever watched one of them on TV blundering over simple legal concepts can only be appalled at their ignorance. Yale must wince even more when their law school grad cannot explain the RICO act or emoluments clause. People who watch ID TV and American Greed have a better grasp of racketeering law than someone like Senator Cruz of Texas, who is apparently lost on the major points to say nothing of the minutiae. Cruz was a product of both Princeton and Harvard Law.

For myself, I was homeschooled from K through 12. Never once during studies was any of my tests, assignments, reading, and etcetera graded with a letter or a numerical score. After graduating high school, I was asked by college applications and some job applications what my GPA was; I had none. When I asked my mom, who herself was a college graduate, she said she valued mastery of the subject over something as silly as a letter grade. In terms of grading, there are collateral issues of fairness affecting grading, such as grading down a paper for being electronically entered one minute late, when the work was clearly done before the deadline.

In conclusion, both authors have valid points on a topic that is relevant to all of us, whether in education or not. Grade inflation does not serve society, the student, the professors, the parents, or the college.

Society suffers from uneducated people that essentially have to be retrained–remedial education on the job, so to speak. This is not so bad in pricing shoes at the store, but I would not want my surgeon asking another instrument to use to remove my gall bladder.

Part of the purpose of a lower grade is to incentivize hard work. Grade inflation removes that incentive.

The student does not benefit when he learns to earn, he learns to whine, he drinks, he learns laziness and bullying, and he thinks he is a winner. He steals home, but he also steals 2nd and 3rd base and thinks he hit a home run. What has he benefited from this scheme?

The professors do not benefit and must feel terrible. Why bother to teach if no one is even trying? Retire with 30 years of graduates and maybe 50 of them are worth much. If they care about education and their legacy, they have this to face. Everyone gets a trophy for showing up, we are all winners, and nothing means much.

The parents do not benefit as they shell out more and more money for a big-name degree for their lazy child and assume that this means they will be successful. Is this money well spent?

Harvard or Brown or Yale become jokes on themselves– oh, they will add plenty of money to their plenty of ivy and all of that, but in the end, they are essentially rich prostitutes. They sold their honor and charge for change, and the world will know it soon enough. Any benefit is temporary and fiscal and, at the same time, dilutes what they once were and meant.

Works Cited

Primack, Phil. “Doesn’t Anybody Get a C Anymore?” From Inquiry to Academic Writing: A Text and Reader. 4th eds. Eds. Stuart Greene and April Lidinsky. Bedford/St.Martin’s, 2018. 69 – 71.

Rojstaczer, Stuart. “Grade Inflation Gone Wild” From Inquiry to Academic Writing: A Text and Reader. 4th eds. Eds. Stuart Greene and April Lidinsky. Bedford/St.Martin’s, 2018. 108 – 10.